17 February 2012

Alessandra Sierra

In the beginning, there was a guy with an idea. That guy was Rich Hickey, and his idea was to combine the power of Lisp with the reach of a modern managed runtime. He started with Jfli, embedding a JVM in Lispworks' Common Lisp implementation. When that proved inadequate, he took a two-year sabbatical to write the compiler that would eventually become Clojure: a completely new Lisp for the JVM with language-level concurrency support.

In late 2007, Rich Hickey presented Clojure at a meeting of the New York Lisp users' group, LispNYC. I was there, and I was so excited by what I saw that I wrote one of the first blog articles about Clojure. Three days later, I was asking questions about Java interop on the Clojure mailing list.

Those early days were fun, participating in heady discussions about fundamental language features like nil vs. false and argument order. It felt like the beginning of something genuinely new. The community was tiny, and Rich participated in almost every discussion on the mailing list or IRC.

How times have changed. The Clojure mailing list has over five thousand members, and we just wrapped up the second international Clojure conference with nearly four hundred attendees. Google Groups tells me I’ve racked up over a thousand posts on the mailing list, which is shocking to me. There are five books and counting about Clojure. People are building businesses and careers on it. Who would have guessed, in 2007, that we would be here in just four years?

(That was a cheap shot. Hi, Stu! :)

In the Summer of 2008, Stuart Halloway started blogging about Clojure. With his co-founder Justin Gehtland, Stuart H. had already built a business helping big companies navigate from ponderous Java development to more agile practices and more expressive languages like Ruby. Stuart H. decided that Clojure was the next big thing. He wrote the first book about Clojure (soon to get a 2nd edition). When he and Rich met at the 2008 JVM Language Summit, they started a long conversation that would eventually become a partnership.

Around the same mid-2008 time frame, "clojure-contrib" began its life as a Subversion repository where community members could share code. There were twelve committers and no rules, just a bunch of Clojure source files containing code that we found useful. I contributed str-utils, seq-utils, duck-streams, and later test-is.

The growth of contrib eventually led to the need for some kind of library loading scheme more expressive than load-file. I wrote a primitive require function that took a file name argument and loaded it from the classpath. Steve Gilardi modified require to take a namespace symbol instead of a file. I suggested use as the shortcut for the common case of require followed by refer. This all happened fairly quickly, without a lot of consideration or planning, culminating in the ns macro. The peculiarities of the ns macro grew directly out of this work, so you can blame us for that.

Clojure-contrib also prompted a question that every open-source software project must grapple with: how to handle ownership. We’d already gone through two licenses: the Common Public License and its successor, the Eclipse Public License.

Rich proposed a Clojure Contributor Agreement as a means to protect Clojure’s future. The motivation for the CA was to make sure Clojure would always be open-source but never trapped by a particular license. The Clojure CA is a covenant between the contributor and Rich Hickey: the contributor assigns joint ownership of his contributions to Rich. In return, Rich promises that Clojure will always be available under an open-source license approved by the FSF or the OSI.

Some open-source projects got stuck with the first license under which contributions were made. Under the CA, if the license ever needs to change again, there would be no obstacles and no need to get permission from every past contributor. Agreements like this have become standard practice for owners of large open-source projects like Eclipse, Apache, and Oracle.

In 2010 I left my cozy academic job and went to work for Relevance, where Stuart Halloway and Rich were discussing a strategic partnership that would eventually become Clojure/core. So what is Clojure/core? It’s a business initiative of Relevance (though not an independent business entity) to provide consulting, training, and development-for-hire services around Clojure. Rich Hickey is an advisor to Clojure/core, but not a Relevance employee.

Members of Clojure/core, of which I am one, have made a commitment to spend their 20% time supporting the Clojure ecosystem. Although Rich still personally reviews every patch for the language itself, the job of answering questions and organizing contributions from a 5000-member community is too big for one person, so Rich delegated that responsibility to Clojure/core.

The first big issue Clojure/core had to confront was the distribution of clojure-contrib. With sixty-plus libraries in one binary release, it was already unwieldy. Since clojure-contrib releases were tied to Clojure language releases, which happened infrequently, development had stalled. There was also vast confusion about what, exactly, clojure-contrib was meant to be. Was it an essential component of the language, a nascent standard library, or a load of crap? (I was inclined to the latter view, especially with regard to my own contributions.)

My attempts at modularizing clojure-contrib within a single Git repository failed to improve the situation. Eventually, we settled on the solution of separate Git repositories for each library. This was a huge amount of work: dozens of repositories to create and hundreds of files to move. Many of the contrib libraries were stagnant, their original authors lacking time to continue working on them.

Finally, almost a year later, the situation has stabilized: contrib libraries, each with its own Git repository, test suite, continuous integration, and independent release cycle. The overall code quality is higher and development is moving forward again.

It was a painful transition for everyone, not least for those of us trying to manage it all and bear the brunt of the inevitable carping. On top of everything else, the whole process overlapped with the release of Clojure 1.3, the first release to break backwards-compatibility in noticeable ways (non-dynamic Vars as a default, long/double as default numeric types).

Our technology choices for Clojure and "new contrib" — GitHub, JIRA, Hudson, and Maven — were driven by several concerns:

to be first-class participants in the Java ecosystem

to preserve the future-proof licensing structure of the CA

to give library developers freedom to develop/release on their own schedule

to ensure changes are made only after a thorough review process

The last point was particularly important for patches to the Clojure language. Clojure is very stable: since its first public release, implementation bugs have been rare and regressions almost nonexistent. Most reported bugs are edge cases in Java interop. But stability has a price: new features come more slowly. The majority of JIRA tickets on Clojure are really feature requests. Rich is extremely conservative about adding features to the language, and he has impressed this view on Clojure/core for the purpose of screening tickets.

To take one prominent example, named arguments were discussed as far back as January 2008. Community members developed the defnk macro to facilitate writing functions with named arguments, and lobbied to add it to Clojure. Finally, in March 2010, Rich made a one-line commit adding support for map destructuring from sequential collections. This gave the benefit of keyword-style parameters everywhere destructuring is supported, including function arguments. By waiting, and thinking, we got something better than defnk. If defnk had been accepted earlier, we might have been stuck with an inferior implementation.

Conversely, the decision to move some libraries into the language, notably my testing library, was probably premature. (Stuart Halloway accepts blame for that one. :) Some of the decisions I made in that library could use revisiting, but now clojure.test is what we’re stuck with.

If there was one mistake that I personally made during the 1.3 migration, it was speaking as if Clojure/core owned Clojure and clojure-contrib. We don’t: Clojure is owned by Rich Hickey, and clojure-contrib is owned jointly by Rich Hickey and contributors. But we are the appointed stewards (and Stuarts!) of the open-source Clojure ecosystem. In that role, we have to make decisions about what we choose to invest time in supporting. Given limited time, and following Rich’s conservative position on new features, that decision is usually "no."

It’s a difficult position to be in. Most of Clojure/core’s members come from the free-wheeling, fast-paced open-source world of Ruby on Rails. We really don’t enjoy saying "no" all the time. But a conservative attitude toward new features is exactly the reason Clojure is so stable. Patches don’t get into the language until they have been reviewed by at least three people, one of them Rich Hickey. New libraries don’t get added to contrib without mailing-list discussions. None of the new contrib libraries has reached the 1.0.0 milestone, and probably won’t for some time. These hurdles are not arbitrary; they are an attempt to guarantee that new additions to Clojure reflect the same consideration and careful design that Rich invested in the original implementation.

So what is clojure-contrib today? It’s a curated set of libraries whose ownership and licensing is governed by the Clojure Contributor Agreement. It could also serve as a proving ground for new features in the language, but this does not imply that every contrib library will eventually make it into the language.

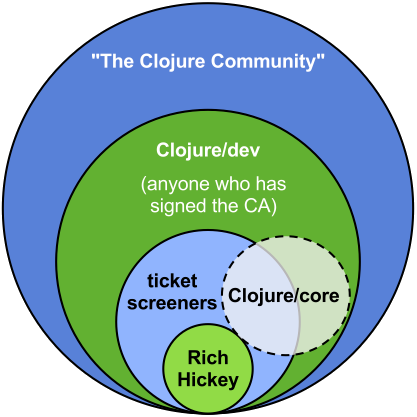

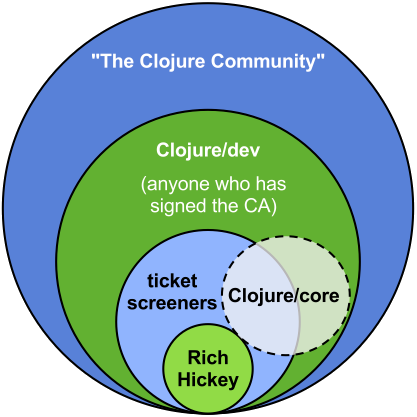

With the expansion of contrib, we’ve given name to another layer of organization: Clojure/dev. Clojure/dev is the set of all people who have signed the Clojure Contributor Agreement. This entitles them to participate in discussions on the clojure-dev mailing list, submit patches on JIRA, and become committers on contrib libraries. Within Clojure/dev is the smaller set of people who have been tasked with screening Clojure language tickets. Clojure/core overlaps with both groups.

At the tail end of this year’s Clojure/conj, Stuart Halloway opened the first face-to-face meeting of Clojure/dev with these words: "This is the Clojure/dev meeting. It’s a meeting of volunteers talking about how they’re going to spend their free time. The only thing we owe each other is honest communication about when we’re planning to do something and when we’re not. There is no obligation for anybody in this room to build anything for anybody else."

One consensus that came out of the Clojure/dev meeting was that we need to get better at using our tools, particularly JIRA. We would like to streamline the processes of joining Clojure/dev, screening patches, and creating new contrib libraries. We also need better integration testing between Clojure and applications that use it. Application and library developers can help by running their test suites against pre-release versions of Clojure (alphas, betas, even SNAPSHOTs) and reporting problems early.

But Stu’s last point is an important one: no one in the Clojure community owes anybody anything. If you want something, it’s not enough to ask for it, you need to be willing to do the work to make it happen. At the same time, don’t let a lukewarm response to ideas on the mailing list dissuade you from implementing something you think is valuable. It might just be that no one has time to think about it. Recall keyword arguments: more than two years from inception to completion. We’re in this for the long haul. Join us, be patient, and let’s see where we can go.