42 ; integer

-1.5 ; floating point

22/7 ; ratioBelow are some examples of literal representations of common primitives in Clojure. All of these literals are valid Clojure expressions.

The ; creates a comment to the end of the line. Sometimes multiple semicolons are used to indicate header comment sections, but this is just a convention.

42 ; integer

-1.5 ; floating point

22/7 ; ratioIntegers are read as fixed precision 64-bit integers when they are in range and arbitrary precision otherwise. A trailing N can be used to force arbitrary precision. Clojure also supports the Java syntax for octal (prefix 0), hexadecimal (prefix 0x) and arbitrary radix (prefix base, then r, e.g. 2r for binary) integers. Ratios are provided as their own type combining a numerator and denominator.

Floating point values are read as double-precision 64-bit floats, or arbitrary precision with an M suffix. Exponential notation is also supported. The special symbolic values ##Inf, ##-Inf, and ##NaN represent positive infinity, negative infinity, and "not a number" values respectively.

"hello" ; string

\e ; character

#"[0-9]+" ; regular expressionStrings are contained in double quotes and may span multiple lines. Individual characters are represented with a leading backslash. There are a few special named characters: \newline \space \tab, etc. Unicode characters can be represented with \uNNNN or in octal with \oNNN.

Literal regular expressions are strings with a leading #. These are compiled to java.util.regex.Pattern objects.

map ; symbol

+ ; symbol - most punctuation allowed

clojure.core/+ ; namespaced symbol

nil ; null value

true false ; booleans

:alpha ; keyword

:release/alpha ; keyword with namespaceSymbols are composed of letters, numbers, and other punctuation and are used to refer to something else, like a function, value, namespace, etc. Symbols may optionally have a namespace, separated with a forward slash from the name.

There are three special symbols that are read as different types - nil is the null value, and true and false are the boolean values.

Keywords start with a leading colon and always evaluate to themselves. They are frequently used as enumerated values or attribute names in Clojure.

Clojure also includes literal syntax for four collection types:

'(1 2 3) ; list

[1 2 3] ; vector

#{1 2 3} ; set

{:a 1, :b 2} ; mapWe’ll talk about these in much greater detail later - for now it’s enough to know that these four data structures can be used to create composite data.

Next we will consider how Clojure reads and evaluates expressions.

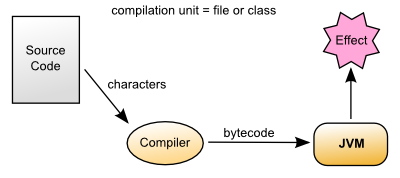

In Java, source code (.java files) are read as characters by the compiler (javac), which produces bytecode (.class files) which can be loaded by the JVM.

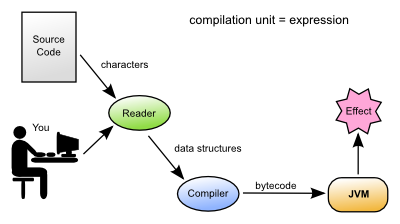

In Clojure, source code is read as characters by the Reader. The Reader may read the source either from .clj files or be given a series of expressions interactively. The Reader produces Clojure data. The Clojure compiler then produces the bytecode for the JVM.

There are two important points here:

The unit of source code is a Clojure expression, not a Clojure source file. Source files are read as a series of expressions, just as if you typed those expressions interactively at the REPL.

Separating the Reader and the Compiler is a key separation that makes room for macros. Macros are special functions that take code (as data), and emit code (as data). Can you see where a loop for macro expansion could be inserted in the evaluation model?

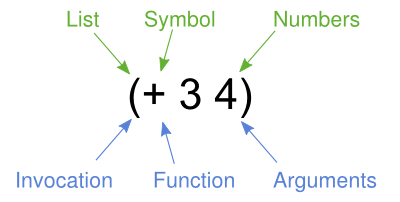

Consider a Clojure expression:

This diagram illustrates the difference between syntax in green (the Clojure data structure produced by the Reader) and semantics in blue (how that data is understood by the Clojure runtime).

Most literal Clojure forms evaluate to themselves, except symbols and lists. Symbols are used to refer to something else and when evaluated, return what they refer to. Lists (as in the diagram) are evaluated as invocation.

In the diagram, (+ 3 4) is read as a list containing the symbol (+) and two numbers (3 and 4). The first element (where + is found) can be called "function position", that is, a place to find the thing to invoke. While functions are an obvious thing to invoke, there are also a few special operators known to the runtime, macros, and a handful of other invokable things.

Considering the evaluation of the expression above:

3 and 4 evaluate to themselves (longs)

+ evaluates to a function that implements +

evaluating the list will invoke the + function with 3 and 4 as arguments

Many languages have both statements and expressions, where statements have some stateful effect but do not return a value. In Clojure, everything is an expression that evaluates to a value. Some expressions (but not most) also have side effects.

Now let’s consider how we can interactively evaluate expressions in Clojure.

Sometimes it’s useful to suspend evaluation, in particular for symbols and lists. Sometimes a symbol should just be a symbol without looking up what it refers to:

user=> 'x

xAnd sometimes a list should just be a list of data values (not code to evaluate):

user=> '(1 2 3)

(1 2 3)One confusing error you might see is the result of accidentally trying to evaluate a list of data as if it were code:

user=> (1 2 3)

Execution error (ClassCastException) at user/eval156 (REPL:1).

class java.lang.Long cannot be cast to class clojure.lang.IFnFor now, don’t worry too much about quote but you will see it occasionally in these materials to avoid evaluation of symbols or lists.

Most of the time when you are using Clojure, you will do so in an editor or a REPL (Read-Eval-Print-Loop). The REPL has the following parts:

Read an expression (a string of characters) to produce Clojure data.

Evaluate the data returned from #1 to yield a result (also Clojure data).

Print the result by converting it from data back to characters.

Loop back to the beginning.

One important aspect of #2 is that Clojure always compiles the expression before executing it; Clojure is always compiled to JVM bytecode. There is no Clojure interpreter.

user=> (+ 3 4)

7The box above demonstrates evaluating an expression (+ 3 4) and receiving a result.

Most REPL environments support a few tricks to help with interactive use. For example, some special symbols remember the results of evaluating the last three expressions:

*1 (the last result)

*2 (the result two expressions ago)

*3 (the result three expressions ago)

user=> (+ 3 4)

7

user=> (+ 10 *1)

17

user=> (+ *1 *2)

24In addition, there is a namespace clojure.repl that is included in the standard Clojure library that provides a number of helpful functions. To load that library and make its functions available in our current context, call:

(require '[clojure.repl :refer :all])For now, you can treat that as a magic incantation. Poof! We’ll unpack it when we get to namespaces.

We now have access to some additional functions that are useful at the REPL: doc, find-doc, apropos, source, and dir.

The doc function displays the documentation for any function. Let’s call it on +:

user=> (doc +)

clojure.core/+

([] [x] [x y] [x y & more])

Returns the sum of nums. (+) returns 0. Does not auto-promote

longs, will throw on overflow. See also: +'The doc function prints the documentation for +, including the valid signatures.

The doc function prints the documentation, then returns nil as the result - you will see both in the evaluation output.

We can invoke doc on itself too:

user=> (doc doc)

clojure.repl/doc

([name])

Macro

Prints documentation for a var or special form given its nameNot sure what something is called? You can use the apropos command to find functions that match a particular string or regular expression.

user=> (apropos "+")

(clojure.core/+ clojure.core/+')You can also widen your search to include the docstrings themselves with find-doc:

user=> (find-doc "trim")

clojure.core/subvec

([v start] [v start end])

Returns a persistent vector of the items in vector from

start (inclusive) to end (exclusive). If end is not supplied,

defaults to (count vector). This operation is O(1) and very fast, as

the resulting vector shares structure with the original and no

trimming is done.

clojure.string/trim

([s])

Removes whitespace from both ends of string.

clojure.string/trim-newline

([s])

Removes all trailing newline \n or return \r characters from

string. Similar to Perl's chomp.

clojure.string/triml

([s])

Removes whitespace from the left side of string.

clojure.string/trimr

([s])

Removes whitespace from the right side of string.If you’d like to see a full listing of the functions in a particular namespace, you can use the dir function. Here we can use it on the clojure.repl namespace:

user=> (dir clojure.repl)

apropos

demunge

dir

dir-fn

doc

find-doc

pst

root-cause

set-break-handler!

source

source-fn

stack-element-str

thread-stopperAnd finally, we can see not only the documentation but the underlying source for any function accessible by the runtime:

user=> (source dir)

(defmacro dir

"Prints a sorted directory of public vars in a namespace"

[nsname]

`(doseq [v# (dir-fn '~nsname)]

(println v#)))As you go through this workshop, please feel free to examine the docstring and source for the functions you are using. Exploring the implementation of the Clojure library itself is an excellent way to learn more about the language and how it is used.

It is also an excellent idea to keep a copy of the Clojure Cheatsheet open while you are learning Clojure. The cheatsheet categorizes the functions available in the standard library and is an invaluable reference.

Now let’s consider some Clojure basics to get you going….

defWhen you are evaluating things at a REPL, it can be useful to save a piece of data for later. We can do this with def:

user=> (def x 7)

#'user/xdef is a special form that associates a symbol (x) in the current namespace with a value (7). This linkage is called a var. In most actual Clojure code, vars should refer to either a constant value or a function, but it’s common to define and re-define them for convenience when working at the REPL.

Note the return value above is #'user/x - that’s the literal representation for a var: #' followed by the namespaced symbol. user is the default namespace.

Recall that symbols are evaluated by looking up what they refer to, so we can get the value back by just using the symbol:

user=> (+ x x)

14One of the most common things you do when learning a language is to print out values. Clojure provides several functions for printing values:

| For humans | Readable as data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

With newline |

println |

prn |

|

Without newline |

pr |

The human-readable forms will translate special print characters (like newlines and tabs) to their printed form and omit quotes in strings. We often use println to debug functions or print a value at the REPL. println takes any number of arguments and interposes a space between each argument’s printed value:

user=> (println "What is this:" (+ 1 2))

What is this: 3The println function has side-effects (printing) and returns nil as a result.

Note that "What is this:" above did not print the surrounding quotes and is not a string that the Reader could read again as data.

For that purpose, use prn to print as data:

user=> (prn "one\n\ttwo")

"one\n\ttwo"Now the printed result is a valid form that the Reader could read again. Depending on context, you may prefer either the human form or the data form.

Using the REPL, compute the sum of 7654 and 1234.

Rewrite the following algebraic expression as a Clojure expression: ( 7 + 3 * 4 + 5 ) / 10.

Using REPL documentation functions, find the documentation for the rem and mod functions. Compare the results of the provided expressions based on the documentation.

Using find-doc, find the function that prints the stack trace of the most recent REPL exception.